Professional theater, especially professional musical theater, is one of the hardest industries to find and hold a steady job. Just because you graduated from a top theater school doesn’t necessarily guarantee a performance job. Maybe you could work hard to get one, but you don’t really know if that’s what you want.

If you find yourself drawn to the world of professional theater, I’m here to let you know there’s much more that goes into a great production besides its actors. How do they look so good on stage? Where’s the money coming from? Who made those over-priced t-shirts you’re going to buy on your way out of the show? Who’s moving set pieces and props on and off stage?

We compiled and researched ten careers in professional theater that don’t involve being on the stage. Read on and you might discover your future.

1. Producers

The producer’s responsibilities include managerial tasks, including managing the productions budget and finances, determining marketing strategies, collaborating with the show’s creative and production teams and following all legal procedures. Producers act as the backbone of the structure of a production. Without their strong management and leadership, productions lose an integral piece of their foundation.

When asked why he made a career in producing, Stephen C. Byrd, award-winning producer and founder of Front Row Productions, said he saw an opportunity to put stories on stage that hadn’t yet been given the opportunity. “There was a lane between Tyler Perry and August Wilson that hadn’t been addressed, from an audience standpoint,” Byrd said. “A number of the classics that I really liked had never had people that looked like me in them, and their stories resonated and had the same context and same experiences that all families of color have.” He seized that opportunity and Front Row Productions has since produced several successful productions including MJ The Musical, Ain’t Too Proud: The Life and Times of The Temptations, and Broadway’s first African American production of Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

According to Byrd, every day is a different day, and the challenges can be never-ending, but he loves the community and the work he gets to do every day. “It’s collegial working with actors and directors, and for me, the best part of the work that I do as a producer,” Byrd said. “You select a team that’s smarter than you to surround yourself [with] to help you execute that vision.” Every production differs, so no matter how successful one production is, the next project’s demands will need a whole new team and different skillsets.

“You try to put together the best people in the field, you do everything that you can, and hope the audience will enjoy it as much as you,” Byrd said. He only produces shows he genuinely enjoys, he says. It makes it that much more enjoyable getting to see the result of a project.

2. Casting Directors

Casting directors hold a huge piece of a production’s success. When they’re hired, they work with a show’s creative team to cast the right people for the production. They’re expected to have a solid understanding of the show, as well as the industry, to match actors to their respective roles. Strong communication, negotiation, and instincts when recognizing talent make an impressive and hirable casting director.

If you study theater, you probably hear at least once a week that you need to make good impressions on everyone you meet because making it in the business relies on connections. A casting director’s business is to know everyone worth knowing in the industry, from groups of both up-and-coming actors and veteran performers. If you make a good impression on a casting director just once, they’ll take note, and you’ll end up one step closer to getting cast in the production of your dreams; or landing your dream job on that casting director’s team.

In order to become a casting agent or director, you need to understand how the professional theater industry works and changes. Experience also helps you get a gig learning from a casting director and their team, so finding one that offers apprenticeships, internships or fellowships would be a great start. Also, most performing arts clubs on college campuses offer student-run productions. So, get involved and you can add a production team credit to your resume (aka, experience for your casting internship application).

3. Theatrical Press Agents

Publicity holds an essential piece of a show’s success; if no one knows that a new show is opening or what it’s about, why would they go see it? Enter: theatrical press agents. They’re responsible for all press that a show needs. They start with the “temple pieces:” a press release, an announcement in the New York Times followed by other major newspapers and setting up a television performance for musicals. From there, agents pitch more stories and work on the publicity to follow, such as photo shoots, filming performance reels and any other pre-opening events.

Boneau/Bryan-Brown, one of the leading theatrical press agencies in New York City, represents many popular shows on Broadway, such as Chicago, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, Moulin Rouge! The Musical and Six. Amy Kass, a press agent with Boneau/Bryan-Brown, began her work through an internship at the company. “I always loved theater, but I never wanted to be an actress or do behind the scenes stuff,” Kass said. “When I was a freshman or sophomore in college, somebody was talking about having an internship at a Broadway press office and I was like, ‘Wow I didn’t even know that existed,’ and I kind of went from there.” She loves her work because she gets to work with many different creative teams with whom they form connections for future projects.

Strong candidates for a future in theatrical press have a degree in journalism, public relations, entertainment business and theatrical management. They carry strong communication skills as well as creativity and the ability to organize various publicity plans. Kass said there isn’t necessarily a typical day, as the work depends on the project and the plan for that project. They act as liaisons between the production’s team and the press. Plus, while these press agents should be good communicators, they also should love the theater!

4. Stage Managers

If you’ve ever participated in live performance, you probably remember the stage manager. The stage manager’s role includes hands-on responsibilities. They work with a show through the entire process: from the very first rehearsal to the final performance. A director relies heavily on the stage manager throughout the process because they essentially run the show once the production adds all the technical aspects.

In rehearsal, a stage manager’s responsibilities include – but not limited to – taking down blocking and staging, assist the director, and making any notes for the technical team. They handle all the of managerial work, such as any paperwork and information for the cast and crew, as well as information for the production: scene breakdowns, prop lists, costume changes, etc. They take note of any design or technical elements the costume, set, and lighting designers need to know about. When a production moves into the theater, a stage manager works with the crew and house staff to ensure everyone knows what to do and how to do it effectively. During the show, the stage manager “calls” the show, meaning they cue any technical effects including lighting, sound, and set. Because they watch every one of the show’s performances, they’re expected to assist the actors as best they can when it comes to changes to their performance, according to Roy Harris, a veteran stage manager on Broadway.

Because the stage manager holds an essential role in a production’s stability, many productions – both professional and amateur – need a stage manager. This opens opportunities for those looking to make a career as a stage manager in professional performance to gain experience before applying for jobs or internships. It’s a very intense role, so all prospective stage managers need experience. Working as a stage manager, assistant stage manager, or just on the production team of a show in high school, college, or regional theaters could launch them in the right direction.

5. Company Managers

A company manager holds similar responsibilities to the producers, but their work focuses entirely on the production’s company, or actors. Think of them as the human resource team of a production. They work with producers to negotiate contracts and salaries, manage rehearsal schedules, arrange any transportation or lodging for touring productions or special events, and much more. Company managers should the ability to problem solve and multitask, all while ensuring the stability of the company and its crew.

The typical day for a company manager of a Broadway production could include a good amount of work in an office, taking care of contracts, payments, and other various managerial tasks. By the end of the day, they visit the theater to relay any work done during the day and ensure the show is running smoothly. If there are any issues within their job description, they’re there to solve them.

Many company managers start out working in stage management or business management. At the end of the day, company managers know how to manage (for lack of a better term). Company management gives them a bit more creativity and control over their day-to-day work, according to Susan Sampliner. Many company managers take on assistants, opening learning opportunities for future company managers and gaining assistance on their responsibilities. Interning with a general management company for theater also helps boost your experience and getting hired.

6. Production Managers

A production manager’s job description aligns with company managers. Production managers focus largely on the crew and production team’s fiscal and construction needs, while company managers focus on the cast and crew’s “human resources” needs. They set budgeting – later funded by the producers – based on the designers’ needs. Once a show has been designed, it begins the construction process. That’s when the production manager’s focus rests solely on the crew and production team. They create a production schedule and work closely with these teams to ensure everything is running according to plan.

Many production managers also start out as stage managers. By becoming a production manager, you continue with many of the responsibilities as a stage manager, but you gain more of a leadership role. The production manager the person in charge of the entire production team and the “bridge between the administrative/artistic teams and the production staff.” A production manager falls more along the lines of the stage manager’s supervisor. They monitor the entire production process and assist where needed.

7. Technical Directors

A technical director (TD) oversees all technical aspects and departments of a show during construction and performance. The person in this position needs to be both a technical expert and a project coordinator. They understand and maintain all technical assets within a production. A part of their responsibilities also includes monitoring safety and advising production managers, directors and designers when applicable. They run their team, comprised of the entire technical staff; they recruit, hire and train this team; and they must know and understand all pieces of the production they’re working on.

The technical director drives the boat. They work makes the director and producer’s vision possible, while maintaining their budget. When shows go on tour, this position directs the traveling of the sets, props, costumes, and other technical aspects of a production. Some bigger shows, like The Lion King, require days of moving sets, so they begin the move to the next city while the cast is still performing in the current city. It’s a symphony conducted entirely by the technical director.

The position of technical director stands as the “apex of a career in technical theater.” It requires many years of experience in the technical field. Anyone looking to become a technical director needs strong management and leadership skills, as well as an advanced knowledge of all technical aspects of a production. Working on lighting or scenic crews on productions act as a solid starting point for any future TDs. It also helps to have an advanced degree in or related to theatrical production.

8. Designers: Costume, Scenic, and Lighting

Other than the director, the designers’ jobs require they know the production inside and out. They consider time period, conceptual ideas for the show, where each scene takes place, the feeling the director wants the audience to feel in specific scenes, etc. Plus, a lot of what they do relies on each other’s designs. The costume designer can’t put a certain character in blue for a specific scene because that scene’s setting contains blue walls. Equally, a lighting designer can’t put the actor in a blue backlight because it will blend in with the set and lose its effect. Everything works together, and these designers work closely with the creative team to ensure that it does.

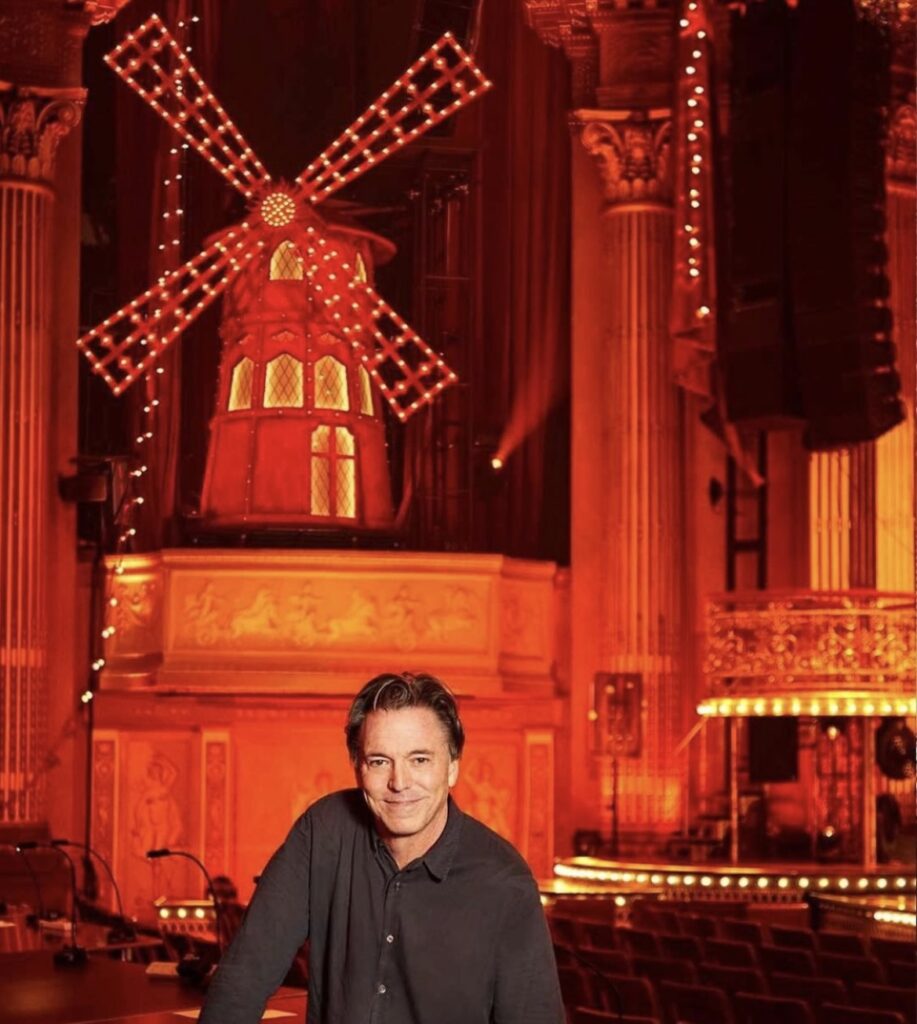

Set designers create the world in which a play or musical takes place. Without their skilled and detailed work on a set, the audience wouldn’t be able to distinguish where the characters are or why. Broadway and Academy Awards ceremony set designer Derek McLane started working in construction in college when someone asked him to build a set. This experience piqued his curiosity in set design, so he began designing and building a portfolio. He acquired many of his early jobs in college by simply telling people he wanted to design, and they let him. He developed some skills and experience doing this in undergrad, but still felt as though he could work on his skills. So, he attended Yale School of Drama and received his MFA in set and costume design.

“I would say my favorite part [of set design] is coming up with ideas, such as initial meetings where we sit and say, ‘What if?’” McLane said. “A lot of times, working as a set designer and doing the earlier work with the director is the process of inventing the logic of that world, and that’s the most exciting part.” That process always begins with reading the script. McLane’s scenic design for Moulin Rouge! The Musical is jaw-dropping, and a lot of what he created came from the script. Because the show starts and ends at the nightclub, he made the entire Broadway theater into the club. “In the script, it has a beautiful description of it,” he said. “It describes the club as just like this: ‘Sex and smoke.’ And so, all I did was I read that, and I was like, ‘I know what to do.’… As a designer, that’s kind of a clue that you want, you know – a really guttural, emotional clue as to what it should look like.” That “guttural, emotional clue” struck McLane with inspiration and creativity, something that prevails in his design.

Award-winning costume and set designer Bunny Christie (set and costume designed Marianne Elliot’s gender-bent revival of Company, and The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time) agrees with McLane’s remarks about the script. She said it’s the first thing she looks at when starting a new project. “The first thing I do is to do a very close reading and make notes on each scene… how it feels, what the atmosphere is, random thoughts I have, time, energy, sound, emotion,” Christie said. She does this work before even meeting in depth with the director.

Christie also said she loves coming up with the first ideas on a new project. “And then I love seeing the design onstage during the fit up and adding lights and sound during tech,” she said. New ideas give her room to freely play with ideas and instincts. She creates images based on her initial instinctive reactions to the playwright’s writing. Christie’s process of becoming a designer also aligns with McLane’s; she said she worked hard building relationships with directors who were doing interesting work. It’s all about connections.

Lighting designer Jeff Croiter said he didn’t see himself being able to make a career in lighting design. He gravitated towards lighting design when he was younger and went on to study it in college, but he still thought he would eventually make a career change. However, just as he thought he was ready to make the change, his love and talent in lighting design caught on.

“I was working, and I was doing it,” said Croiter. “I was having the kind of success that I wanted, so why walk away from that, I guess.” Croiter also noticed what drew him to theater, specifically: he enjoyed the people. “So much of why I joined this business and still am a part of this business is because I enjoy the people I work with,” Croiter said. “So much of it is about the people.”

Croiter also said he loves working in theater because of the audience reaction to something he’s worked on. “In Newsies, at the end of that first big number, when the music ends and the lights pop up on the kids all posing and the audience loses their mind, there’s nothing better than that for me,” Croiter said. “I mean, at the end of the day, it’s not for me, it’s for someone else.” His continued work in the field follows the reason he said people often forget when working in theater: it’s for the audience.

9. Dramaturgs

As a continuously evolving art form, dramaturgy holds a growing importance in modern theatrical performance. A dramaturg’s role takes place mostly behind-the-scenes, working to provide research, questions and insight typically on developing works. Their work improves the production’s quality and accuracy. Berklee.edu said, “Dramaturgy is a flexible career that often means a mix of office-based work, independent research and reading, participation in rehearsals and post-performance talkbacks, and time spent off the job discussing plays and networking with the other like-minded dramaturgs.” They provide their work with the creative teams and cast to improve the performance and structure of the production.

Anne Hamilton — dramaturg, writer and playwright — founded Hamilton Dramaturgy; an international dramaturgy consultancy based in New York City. “It’s such an all-encompassing and exciting art form,” Hamilton said. “You’re doing all these amazing functions with learning the material, trying to gain insight and having a personal response to it. Then, work with a team to get that play onto the stage through all its stages: developing it with the actors, directing it, developing the designs, all those things.” Hamilton said learning is part of the job, and it never stops.

Hamilton mostly works freelance and through established connections with career professionals. She finds out exactly what her customer would like her to do, and she gets to work. “You do your best job, you support the other artists who are doing their thing and you also work on your own artistry,” she said. “You try to do right by them so that they can feel safe and have a safe space with someone who is supporting them.” This support and collaboration assists with the eventual stage of production – one of Hamilton’s favorite parts of her work. The production stage involves putting the work on its feet with all of the creatives involved.

Hamilton, along with her coauthor Walter Byongfok Chon, wrote a textbook called “Dramaturgy: The Basics” to be published soon. They hope the book will act as a starting point from dramaturgy students and maybe even open more doors for dramaturgy programs in universities across the country.

10. Intimacy Directors/Coordinators

Though intimacy direction is still a relatively new practice, it has become an integral part of theater performance. Intimacy directors (also referred to as intimacy coordinators or choreographers) create a safe and effective environment for intimate stage work, such as sexual scenes. These can be incredibly vulnerable scenes, so the intimacy director works to make the work as natural and comfortable as possible. They choreograph these scenes to provide effective and accurate storytelling while maintaining a safe environment for the actors. They also act as advocates for the actors in their work.

Intimacy Directors and Coordinators (IDC), a leading group of professionals, provides a space for productions to hire an intimacy director as well as train future intimacy directors and professionals. Their team played a pivotal role in the creation of the fields of Intimacy Direction for the Theatre and Intimacy Coordination for TV and Film. According to their mission statement, they strive to educate and prepare as many theatrical institutions as possibly for all staged intimate work. “Our vision is a world in which intimacy is a vital and joyful part of storytelling, and all artists are able to work consensually,” says IDC; “bringing their whole selves to the work and honoring one another’s individual humanity.” Consent remains the core of these professionals’ practice. Without consent, the actors lose their safe space on stage – a place where many actors go to retreat their “real” lives.

Becoming an intimacy director requires training, leading to certification in the practice. IDC offers certifications in both theater and film and TV intimacy coordination. Their 10-week online course offers enough training and information for prospective intimacy directors to figure out if they’re on the right path. Either way, prospective directors can end with a certification. If they lean away from becoming an intimacy director, they can finish their training with a “Consent Forward Artist Workshop” and a final assessment, earning them a “Consent Forward Artists Certificate.” If they feel they’ve made the right choice with intimacy direction, they can apply and interview, go through a mentorship and complete a final assessment for their certification in professional intimacy direction or coordination.