It’s easy to project our expectations of what sex, gender and sexual orientation should look like onto people—especially if they appear to fit the part. For example, I identify and express as a woman. For the last three years I’ve been in relationships with people who identify and express as men. For these reasons, most people I meet, and even people I’ve known for a very long time, assume I’m straight. But I’m not.

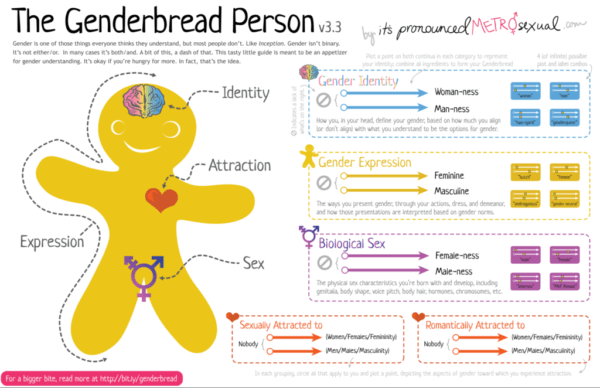

Generally, society and the media commonly misunderstand, misrepresent and misdefine bisexuality. You’ll usually encounter two definitions. The first describes bisexuality as sexual and/or romantic attraction to both males and females. This definition fails pretty spectacularly, though, since it remains unclear what is meant by “male” and “female.” Does this refer to people who identify with those genders, or those assigned those genders at birth? How does this conceptualization address people who don’t identify as either male or female, or who might identify with either one at a given time? Short answer: it doesn’t.

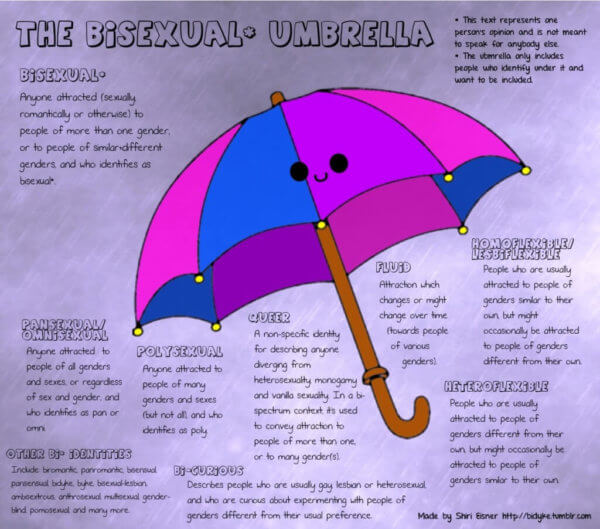

This first definition relies heavily on a binary concept of gender, which has become increasingly obsolete as public visibility, awareness and acceptance of gender nonconforming individuals has increased recently. “Male” and “female” alone do not appropriately describe a large number of people. Sex and gender aren’t that simple. So, some people prefer to define bisexuality as sexual or romantic attraction to all sexes or gender identities, or irrespective of a person’s sex or gender identity. This definition is also sometimes known as pansexuality.

I’m not trying to imply that either one of these definitions is better or worse than the other. I prefer to describe myself as bisexual as opposed to pansexual even though I do not ascribe to a binary concept of gender. I partially prefer this term due to the fact that a lot of people don’t know what pansexuality is and, as a result, love to ask me intrusive questions about it. I find that people feel generally more comfortable with the term bisexual. As a result (that I’m not very happy about), I’m more comfortable using it to describe myself.

This article marks my first public “coming out,” but I generally feel comfortable coming out to people on an individual basis. I come from a liberal California city and go to a liberal California university, so my experience coming out to people has been overall very positive. That’s not to say it hasn’t been challenging. People often respond to my coming out with incredulity—which I understand but, to this day, find difficult to deal with.

As I mentioned before, my last two relationships have been with men, I have a typically feminine physical appearance and no one at my college has ever seen me play the dating game. All of my relationships with other women have also taken place on the down-low, and before I’d met anyone I currently attend school with. People tend to assume that because I “look straight” I am straight. But they make this assumption based on an insufficient amount of information.

Most of the time when I tell a friend or acquaintance that I’m bisexual, they respond with something to the effect of, “Really?” or “But you’re dating a guy,” or “I wouldn’t have guessed that.” I once came out to a classmate and she informed me that I was, as she put it, “effectively straight.” As if my sexual orientation depended entirely on the gender of the person I was currently dating. I never corrected her, because I didn’t particularly care what she thought of me or my queerness. At the time I didn’t really consider my bisexuality a definitive part of my identity as a person.

But the conversation I had that day demonstrates a problem that I believe a lot of bisexual individuals face, both within and without the LGBT community. (Let me preface by saying that I am in no way trying to speak on behalf of the entire bisexual community. These perceptions are based solely on my personal experience and research.) Bisexuals tend to have their sexuality questioned—not necessarily more or less than other LGBT individuals, but in different ways.

For example, a widespread underlying belief that bisexuals just haven’t decided or arrived at their “real” sexual orientation yet, and exist in a sort of limbo between more “legitimate” extremes on the sexual orientation spectrum persists in our society. While some people do identify as bisexual before later identifying somewhere else on the spectrum, bisexuality should be regarded as its own legitimate sexual orientation—not a term to describe partially closeted individuals. When I come out to someone as bi and they point out that I’m currently dating a cisgendered man, they reduce my sexual orientation to the identity of my current partner and invalidate my identity as bisexual.

My romantic partners have also often ignored or invalidated my bisexuality within my romantic relationships—particularly partners that identify as men. For example, my men partners have often expressed feelings of jealousy because of relationships (romantic, sexual or not) I have/have had with other men, but not with women. None of my men partners have complained when I spend time with other women, or even alone with another woman. But if I hang out with a man or group of men I get, “Why do you have so many guy friends?” Most of my male partners have also expressed that they wouldn’t consider my having sex with another woman cheating. Basically, the men in my life believe either that I’m not legitimately attracted to women, or that my relationships with other women are less important or less “real” than my relationships with other men.

Beyond the tendency to ignore bisexuality as a legitimate sexual orientation, there exist a number of harmful stereotypes surrounding bisexuality and bisexual individuals. People sometimes believe that bisexuals are inherently more sexually promiscuous and therefore more likely to have polygamous relationships, cheat on partners or engage in three-ways. For these reasons people also believe bisexuals cannot maintain healthy, long-term relationships—a myth for which I spitefully offer myself as a counterexample.

At this point I shouldn’t have to remind anyone that stereotypes are not only factually untrue, but also detrimental to the individuals at which they are directed. “[Stereotypes surrounding bisexual individuals] may make the individual feel less safe in revealing their identity, and less understood by others. Bisexual individuals are also subject to the jokes, insults and antigay comments or behaviors that lesbian and gay individuals face,” said Kim Elsesser, Ph.D. and psychology and gender lecturer at the University of California, Los Angeles. “This can lead to greater depression and more drug use [in targeted individuals].” Stereotypes also tend to dehumanize the people they target, thereby perpetuating the mistreatment of them and others in their communities.

I’ve never believed anyone who implied that my sexual orientation isn’t legitimate or that I’m incapable of having serious relationships because of it. I know myself and my sexuality well enough to know that people can’t put me in a box and tell me what it means to be in that box. I don’t think that people’s misunderstanding of my sexual orientation has deterred me from coming out to people, either. But it’s definitely made it more difficult for me to embrace and explore my bisexuality as an integral component of my identity. It’s a part of myself I downplay when I want it to be something I cherish and nurture, the same way I think anyone would want to cherish and nurture their own sexuality.

Providing your LGBT loved ones strong allyship is not as difficult or demanding as you might believe. Acceptance is key, but feel free to refer to these resources for more information and support:

Resources:

Getting Bi in a Gay / Straight World

List of LGBTQ+ Vocab Definitions

A Few Ways to Be Better Allies

Examples of Heterosexual Privilege in the U.S.