The first thing you learn in another language is how to say I don’t know. These words offer a reprieve, a mutual understanding between two people, despite their language barrier; but its irony isn’t lost on either individual. I only know enough of your language to tell you I don’t know it. These three little words speak volumes.

I didn’t know the exact Chinese translation of “I don’t know.” That, too, spoke volumes of a different kind.

Though my mother is Chinese, I didn’t know anything about the language. Vaguely, I knew that Chinese wasn’t just a singular language; like any other language, it branched off into other sectors, dividing into several different dialects. And I knew none of them.

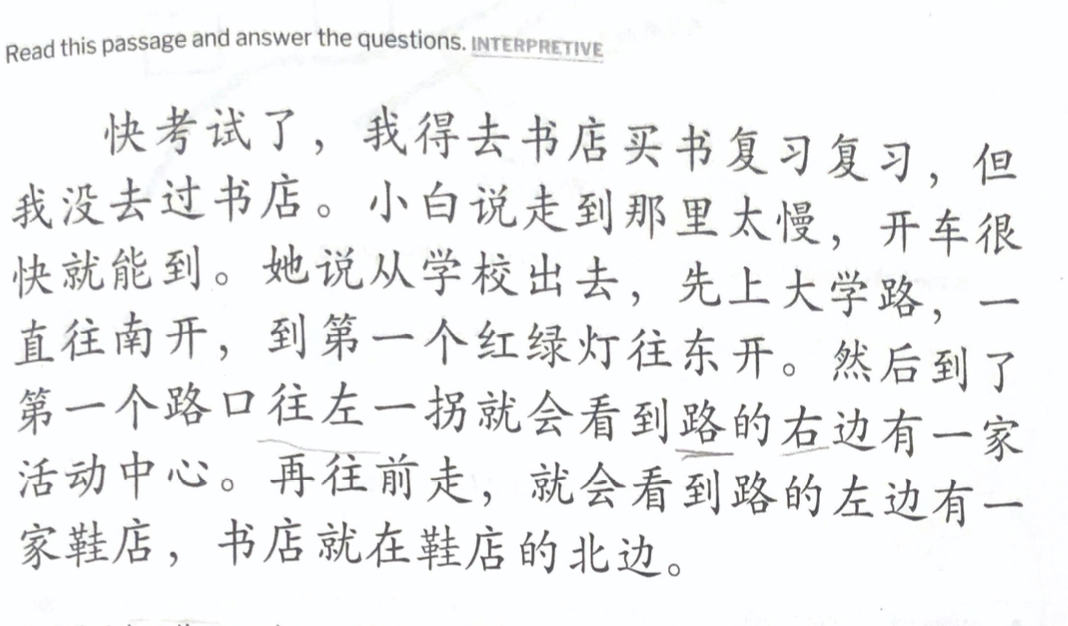

For most of my life, this didn’t bother me. But by the time I began my senior year of high school, I felt out-of-place. When I opened my mouth to speak, only clunky letters of English tumbled out. On paper, I couldn’t decipher Chinese characters—I’d trace my gaze over the writings, studying the strokes but missing the meaning underneath. When people spoke, I listened intently, yet I couldn’t make sense of it. In truth, I felt disconnected from my heritage. I didn’t understand the language, I didn’t understand the traditions, I didn’t understand such a significant part of my personal history.

I felt like an outsider looking in: someone who should’ve grasped it, but never did.

Courtesy of Kyra LaFitte

Language often serves a bridge for understanding culture: it connects you to traditions and stories. That’s what I believed, anyway. So, when I started college, I signed up for Mandarin lessons. I couldn’t exactly predict the difficulty level; people claimed Mandarin was one of the hardest languages to learn. I’d tried learning Mandarin on my own, but the lessons always flew out of me. I hoped a classroom might change that.

I just needed to start somewhere so that the words would cement themselves into my brain.

It did. Kind of. The first few lessons weren’t very difficult, we learned the basics: hello, my name is…, what’s your name? As the lessons steepened, however, so did the vocabulary and grammar. Learning Mandarin is almost like learning two different languages at the same time: you must learn the characters as well as the pinyin, the written form of the word.

Sometimes I could recall the characters but not the pinyin, or vice versa. Often, I stumbled my way through a sentence by recognizing the characters, but sometimes I still found myself stumped. Chinese-to-English dictionaries didn’t really help, because if I forgot a word, I had to flip through the whole book just to find it.

But the real challenge, I found, lay neither in writing or reading. It lived in speaking.

Mandarin possesses four basic tones: first tone, second tone, third tone, fourth tone. Each one sounds different, unique. Hard as I tried, I just couldn’t wrap my tongue around the tones. I pitched my voice high, I practiced alone in my dorm, I went to the tutoring center—but nothing fixed it. When I stressed over how to say something, words would occasionally slip from my brain, and I’d forget something crucial.

My speeches sounded awkward and gaping, the words sliding out all wrong. One of my teachers even pulled me aside to do some extra reading, trying to perfect my speaking. No use. My Chinese sounded nothing like her clear and precise pronunciation.

I’d wanted to learn Chinese to get closer to my heritage, but I still felt miles away from it. A part of me believed that even if I did learn the language, my terrible pronunciation would betray me.

Attempting to cross that bridge was harder than I thought.

Towards the end of my fall semester sophomore year, I needed to decide if I wanted to continue taking on the workload, as Mandarin classes occupied a lot of time and space on my schedule. I was torn: I needed to focus on classes specifically for my major, but I didn’t want to give up. To back out seemed cowardly but there seemed no other choice.

So, I parted with Mandarin for spring semester. It wasn’t an easy decision—even after planning my schedule, uneasiness rested in my heart. I felt like I’d buckled under the pressure.

Shortly after this decision, I visited my grandmother. I told her about my Mandarin classes and why I decided not to continue anymore. Even so, she was excited that I’d taken a few classes, even though I planned to stop. She told me that she used to speak Cantonese, but since my grandfather spoke a different dialect, she’d stopped speaking it. As a result, the rest of my family never really learned the language. But she seemed so genuine, so delighted, that I’d attempted to study the language—a weight (somewhat) lifted from my chest.

I didn’t understand Mandarin as well as I hoped.

But I’d learned a few connections with my own family. In a way, language did act as a bridge—it tied me closer to the ones I loved. I didn’t need to possess perfect fluency skills; the fact that I tried worked well enough. I made peace with my younger self–though my skills were rather wobbly, at least I possessed them. That proved its own worth.

You don’t need to be perfect at a language to feel closer, to understand a part of yourself. Fluency is the dream goal, but it’s okay to not speak fluently, too. The importance lies in your understanding of it. Through that, others will understand you, too. And true to form, language does act as a gateway into understanding culture. You learn so much, even if your skills seem inadequate. Carrying that language in your heart takes you deeper into cultural traditions and understandings. All you need is that bridge.