For many story-loving creatives out there, one of the biggest goals to pursue besides avoiding the starving artist trope fruitlessly, would be publication. Regardless of how successful it may turn out commercially or publicly, just the mere product of a finished book can be a grand achievement to behold!

However, it’s not always easy to get a straightforward answer whenever the more curious creatives ask how exactly to go about said goal. So in this article, I ask five common questions surrounding publication and writing I hear (and wonder) often, to these five published and well-renowned UCLA professors!

In no particular order, we have:

Michelle Huneven, who graduated with an MFA from the University of Iowa. She has 5 novels to date, with her most recent publication being “Search”!

I’ve also taken a creative writing class of hers before, highly recommend.

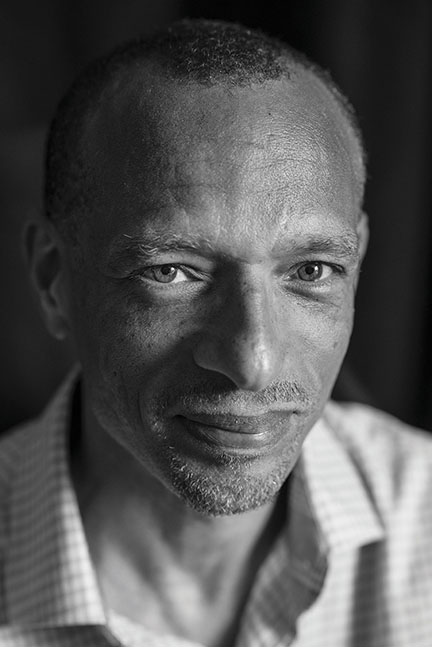

Frederick D’Aguiar, with a Bachelor’s from the University of Kent. A professor with five star ratings in all his classes on Bruinwalk (which is way more impressive than you may realize), he currently has 6 novels and 8 books of poetry!

Eric Jager, graduated with a B.A. from Calvin College and a Ph.D from the University of Michigan. “The Tempter’s Voice” and “The Book of the Heart” were two scholarly books he published before his medieval true-crime books, “The Last Duel” and “Blood Royal”.

(And if you’re cultured unlike me, you’ll know that “The Last Duel” recently got adapted into a movie directed by Ridley Scott). Crossing my fingers for a class with him next quarter!

Mona Simpson, graduated from UC Berkeley and Columbia University with a B.A. and M.F.A. respectively. She has 6 novels, and one of them–“Anywhere but Here”–became adapted into a movie directed by Wayne Wang. She also has a new book coming out later this year! (Keep your eyes and ears open…)

Harryette Mullen, graduated from UT Austin with a B.A. in English, and UC Santa Cruz with a Ph.D in literature. She has several poetry collections to date, and short stories published in anthologies such as “Her Work”, “Common Bonds”, and “The African American West”.

Coming this December, she’ll be having yet another get published by the Indiana Review, so make sure to mark your calendars!

Now, onto the questions:

1. The gap between writing and publication can be dark and blurry… What light could you offer to shine on said gap?

One overall tip many offered on how to get the ball rolling on this foggy path, is to establish a community of writers for yourself.

Huneven spoke on the importance of community,

“I think what helped me the most, was when I went to grad school, I formed a community of friends there. Those friendships later continued outside of grad school, and I made more writer friends.

“People think that maybe it’s their professor in college or grad school who’s going to get them their break–but it’s really their peers. That’s why I tell my writing students to get into writing groups and make fast, good friends with other writers, because they’re the ones that’ll get that job in a magazine, and then they’re gonna say, ‘Oh I know the perfect person to write that article’ or ‘I know someone who’s writing a really good short story’.”

D’Aguiar also emphasized joining any writing circles you can, and how “It’s worth checking the notice boards in your classes or dorms, see who’s having author events. All while you keep up your own writing, even if it’s by diary.”

Which leads to our next general bit of advice: take advantage of your school campus.

While Simpson was in graduate school, she worked at a fairly established literary magazine, but she mentioned that, “Some writers, instead of doing that, actually started their own magazines. So I think instead of asking ‘how do I publish’, the question should be ‘how do I make a life, as a writer’.”

Taking initiative can be difficult of course, but doing so will certainly show your dedication and talent when it comes to pursuing writing!

Simpson continues, “Centering writing in your life, like making sure your apartment is quiet enough for you to focus for example… I think the more you do that, the more your writing will really grow. And sooner or later (hopefully sooner, but sometimes it’s later), you’ll meet other people who are serious about writing, and then publication will follow.”

Jager himself “…wrote for various campus publications in college, valuable practice that also brought me into a community of writers. But the publishing bug really bit me in grad school, and I aimed at scholarly journals as well as more popular venues. For the next decade and more, I wrote mainly academic books and articles, focused on earning tenure and establishing a career.”

It was also during this time that Jager “stumbled over a story in a medieval chronicle, about a 1386 trial by combat, that I sensed had great commercial potential.” Inspired, he took to researching the event, and as you all probably know, writers can take their research very, very seriously. “Beginning in 2001, the research took me and my wife, Peg, to Normandy and Paris, where I ransacked the archives for documents and we visited castles and estates that figured in the story. It was my third book, but my first one for a popular audience, and there was a lot of on-the-job learning. I had to lose the theory and jargon that plague the academic humanities and keep my eye on the story, the characters–and that Norman landscape.

“A very good editor helped, and so did Peg, who read every page of the manuscript with an eye to a popular audience. Fortunately, a very good literary agency in NYC saw the story’s potential as well. In one giddy week they sold the book at auction to Random House, and interest in the film rights soon followed.”

Mullen additionally notes the great significance of the internet, concluding, “So really, there is no gap, you can publish instantly”, which is a far cry from “When I was coming up… you know, you’d send your poems out in an envelope with a stamp. Now, you all have many more opportunities, more choices, more platforms to use for your poetry.”

Of course, there can be some pros and cons to this, “..since instant isn’t always the best thing when it comes to creative writing. Sometimes you need to let things sit for a while and come back to them later.” Not to mention, with how widely accessible the internet is to so many people, it’s not uncommon when “your work can be found in searches by people who may or may not be interested in your work per se.”

Regardless of how or where you decide to publish, one paramount question Mullen brings up is: “You need to think about why you need to publish. Why are you writing, what do you want to do with your writing, or what do you want your writing to do in the world?”

Everyone will have their own unique reasons (mine is that my brain simply offers me no choice in the matter, rip), and understanding your goals is almost just as important as understanding your main character’s goals. In both cases, reaching the end will be difficult without that mental map in mind.

“Some people write for their own benefit, like writing therapeutically, exorcising my demons, getting something off my chest… You can write without publishing, only sharing your work with a few dear friends or family, or on broadsides and just pass them out at a rally.”

Now, I can hear a few of you going, “Well that’s all banger advice but, what about the more technical side to publishing?”

Well, Mullen goes to detail a bit of that side, explaining how,

“There’s different tiers of publishing.. there’s commercial publishing, academic publishing, there’s small presses, independent presses, vanity press–and that’s the only one I would warn against. Vanity publishing is paying someone else to print your work, they don’t really ‘publish’ it. They just print it, and they may or may not advertise it. And they usually do not distribute it except to you (or if you give them a list of people) but you pay for that.

“Then they send you a stack of books, and it’s your responsibility to promote, distribute, sell, giveaway, whatever you wanna do with this stack of books. I mean I’m not saying no one should ever use vanity presses, but to me it’s a waste of money when you could publish your own work for a lot cheaper and distribute it yourself anyway cause that’s what you’ll be doing.”

Clearly there are many different paths to publication out there, and that can be overwhelming. But the general consensus among our expert board seems to be:

Connections, community, and your own resourceability will take you far. Seek out experience through others and yourself (in other words, write write write!). And as Mullen aptly summed up, ask yourself, “Anytime you want your work in print.. why? And for whom?”

2. Agents. Do we hunt for them or not?

Agents are a common subject to hear of in the realm of creative arts, but there often seems to be some mystery shrouded around the topic. How exactly does one go about agents at all?

Simpson shares, “I didn’t hunt for an agent.. I actually found her sort of by accident. I had sent a story to the Atlantic Monthly, and a young editor liked it. His boss didn’t buy the story in the end, but the young editor had a friend who was an agent, looking for clients, so he gave her my story. She called me out of the blue, that was lucky.” You win some, you lose some!

“I was in graduate school. She took me out to lunch in a restaurant with a circular red leather booth. It was my first winter in New York, and I didn’t have properly warm clothes yet. She flung her fur coat over the banquette; it was all very glamorous and at the end she said, ‘Well if you write a novel, call me’.

“I did write a novel and I did call her, but it was 6 years later… Other writer friends have found agents by seeking them, though I think the best thing to do is to find an agent after you start sending out your stories and publishing a few first.”

D’Aguiar agrees, commenting, “That’s early. It’s unusual for undergraduates to have an agent. You only need an agent once you have a book. Before any talk of agents, it’s good to join campus magazines or apprenticeships, for the experience of having editors talk back to you.”

For those still sadly bookless like me, Huneven’s words of wisdom were: “For a long time I had agents who were interested in me, but I had nothing to show them. When you have something to show an agent, something they can sell, they’ll be interested. Of course, it’s helpful if you have friends that have an agent–it’s always connections.

“When I was teaching in Iowa ten years ago, agents would come to visit. And my students there would say, ‘I don’t have anything to sell, why should I talk to this agent?’ And I said, ‘Because even one conversation is the beginning of a relationship.’

You can later write to them and say ‘I talked to you in Iowa City two years ago when I was just starting my novel, and here it is.’ And they’ll be interested in that. So again, it’s a sort of web of peer connections, and school helps.”

Quick callback to when D’Aguiar mentioned checking your school’s notice boards! Many clubs have speaker events, and if they don’t showcase agents, most are more than willing to receive suggestions on who to bring next.

Huneven adds, “Agents will tell you when they’re accepting and reading new manuscripts. It’s always good to go to young agents, cause they’re really hungry. They’re looking for somebody undiscovered that they can push. I would go to young agents, new agents, or agent assistants.”

What if you’re not sadly bookless like me? Jager offers some active advice, “Unless you have a referral, it’s mainly trial and error. My suggestions: read Publishers Weekly or subscribe to Publishers Lunch to learn about the latest deals and who’s buying what. Study the acknowledgements pages of books similar to your own for the names of prospective agents and editors.

“Then write a short, direct query letter that will make agents sit bolt upright as though a gorilla just charged into the room. To change metaphors: The query (who you are, what your book’s about, why it will sell) should whet an agent’s appetite for the proposal, and in turn for the manuscript, completing a tasty three-course meal. A bland query won’t make her salivate for the next course; and a half-baked proposal won’t make him stick around for dessert. Serve every sentence of each course as though your publishing contract depends on it — because it does.”

When it comes to our resident poets however, things could be a little different, as Mullen explained, “Poets don’t have agents, period. Unless you also write in another genre, you will never have an agent. What you might have is a speaker’s bureau. If you become a very highly acclaimed poet, meaning someone who’s published multiple books, won or have been nominated for national or international prizes (and someone who is not totally crazy bonkers), you may be approached by speaker’s bureaus. They function as agents for your speaking and reading engagements, not your books. You don’t need a literary agent, because everyone who publishes poetry is losing money. The poet is losing money, the publisher is losing money, the bookstore/bookseller is losing money.”

Perhaps I should change the “starving artist” trope earlier to “starving poet”… kidding!

“Now I don’t mean to be discouraging. Cause I’m very fulfilled having a job that supports me, and then I can write whatever I want because I don’t depend on my writing for a living, which gives me a greater freedom that I enjoy. If you have a job that nourishes your body, then you can write whatever nourishes your spirit.”

Simpson nods to this, “I mean, poets have always understood that being a poet is not going to be income-generating in the way that, say, being a banker or an insurance agent is for, well, rent. Poets understand that they have to somehow make a living in such a way that will allow them also to write poetry.”

Which leads to our next question…

3. For those with more financial concerns (AKA me), would you agree that one shouldn’t pursue a writing career while writing creatively on the side?

Before this interview, whenever I asked a published author this question, they always advised against writing for a living, while also writing your personal projects on the side. Burnout and all.

If you’re like me… writing is all we CAN do! It’s kind of my only “thing”, and I’m not exactly rich either (the opposite frankly) so, what then?

Jager’s answer: “I’m not sure they’re mutually exclusive. After graduating from UCLA, one of my best students in recent years got an internship at a small indie publisher in NYC that soon turned into a permanent job. After a year or two, he took a position at a big trade publisher. He’s now living his dream amid the New York publishing scene and writing on the side. A lot of young editorial assistants apparently write on the side and nurture dreams of publishing their own stories, essays or books. And you don’t always need an expensive MFA to do so. Working as a barista may actually teach you more about life and human nature. Good writers are endlessly curious and often largely self taught. They read constantly and are quick to learn from each other.”

Most shared the sentiment, especially when the career had to do with article publishing or journalism. D’Aguiar shared, “A lot of writers are working on their own projects, while also writing articles about books… I’d say that’s complementary actually. Cause it gets you reading. To write about things you have to read.”

Simpson could speak to journalism, “It’s harder to be a journalist these days than it was when I was younger, but I think it’s a good idea because deadlines teach you not to wait for inspiration but to just get down to work.

“I mean, any way of life you can suggest, some writer done it. It depends on the temperament. Some people are happy working in publishing, where they’re near all the happenings of the writing world. Some people like to be a million miles away. The key is to find out what kind of person you are, what works best for you.

“I do think it’s important, one way or another, to find a writing community. Either a writing school or a summer program, anywhere.”

Huneven had made her living “…for years and years as a journalist before I started teaching. I actually found that journalism–or the kind of journalism I did–was really good for my writing.

“In England they have a different model; writers write anything. They write reviews, they write magazine pieces, they’ll write anything to make a living. Here in the United States, there’s a kind of sentiment like ‘Oh I would never write that. I’m a fiction writer’. I never thought that, I liked writing journalism, it kept the juices flowing. And it taught me how to not be perfectionistic.”

It’s good to stay mindful of certain trends in careers related to writing, as Huneven also agreed that “it’s gotten harder to make a living as a journalist since the web. Articles I was paid a thousand dollars for, I’d be lucky today to get two hundred dollars. Newspapers don’t make the money that they used to.”

Huneven adds, “There’s a lot of money to be made in television right now. You make a lot more writing for TV, and because of that some of the best writers are doing TV part time or full time.”

Overall: “I don’t think it hurts to have a professional job and be a writer. Because the chances of supporting yourself as a writer are slim. So why not train yourself to do something that will earn you a comfortable living? I was always a freelance writer, I’m still kind of a freelance teacher, and I kinda regret that I didn’t go to law school, you know? I thought that a bigger part of my life would be writing. And I’m lucky that it has been, but you also want to be able to live and support yourself.”

Or in other words, “You just cobble together a life around your writing.”

Mullen replies, “I think that very much depends on circumstances. Who are you as a person, how much energy do you have, how much could you compartmentalize your brain, what other responsibilities do you have? I think it’s probably easier if you don’t have dependents, or if you’re able to move around freely, or work online/remotely. I think people who can travel are much more flexible for all kinds of jobs, especially if you’re doing freelance work. Gotta be flexible, able to delegate, compartmentalize, and be very organized and disciplined.

“My sister was writing freelance while raising kids–and it was very difficult for her. And she was only doing it as a part time gig, she wasn’t depending on that money, her husband was more the breadwinner for that family. A lot of those jobs are not secure; she would have to write a query to an editor, there’ll be a bit of back and forth on whether they’re interested in your query, maybe they’d want you to write more, maybe send them a sample, negotiate what the price will be, sometimes they’ll solicit your work and then not publish it, and they may or may not pay you for it. If they pay you, they call that a ‘kill fee’, but it’s less than what you would’ve gotten if they had published it… There’s a lot of ‘business stuff’, and you have to do it over and over and over again if you are a freelancer.”

Simpson also extended caution, “Sometimes fiction writers are able to make a living and sometimes they’re not. It depends on the work, one’s flexibility, how much of what you’re interested in happens to chime with what the publisher wants at any given moment–very little of that depends on how good the work is.

“So I think it’s a good habit to figure out, let’s say, if you don’t make a living by your writing just yet… How are you going to fashion a life where you can still put writing at the center? You get out of school and all kinds of different ambitions and claims find you, so you need to make sure to make room for writing to be the central mission in your life.”

4. Any specific advice for UCLA’s creative student body (or for confused writers everywhere)?

Bruin or not, get ready to take notes!

Harryette Mullen: One of the things every writer has to figure out is how are you going to integrate writing into the rest of your life? That would include fitting your paying job into your life as a writer. That is a juggling act that everyone has to perform at some point.

Frederick D’Aguiar: Read. Read as much as possible. And I think for UCLA.. I’d tell students to get involved with Westwind. You can get a lot of insight to publication there.

Michelle Huneven: My advice is always the same: set the timer for twenty minutes and write every day. Everybody can do it, it’s only twenty minutes, just do it. You’ll be surprised how fast the pages accumulate, and how good you get. And if there’s somebody you can read those pages to everyday… again, it’s that community of writers that’s so important. It’s your friends who bring you along with them, not the teacher, not the person above you, it’s the people around you. You’ll get better so fast.

Mona Simpson: Find each other. Read as much as you can. Find the literature that excites you the most. Find other people whose work you respect and who share some of the same dreams. And I think the most important thing: make a life where writing is always at the center. Make friends who think that you being a writer is a great idea. Richard Ford once said, marry somebody who thinks that you being a writer is a good idea.

Eric Jager: A few years ago I was invited to speak to a CW class, and this is how I concluded:

We writers are like fish, all swimming around in the same great ocean of literature, which gives us life and motion, society and food. Saying you want to be a writer without reading — that’s like saying you’re a fish out of water. You know what happens to a fish out of water. It dies. So read, and keep reading. Keep immersing yourself in the life-giving ocean of literature.

Here’s a practical tip. When you read a passage that makes you sit up and say, “Wow!” — stop for a moment and ask yourself: how did those little black marks on the page do that? How did they make me see something in a fresh, new way? Or make me laugh, or make me cry?

Study that passage. Analyze it. You’re smart; you’ve been taking lit classes; you know something about diction and syntax and metaphor. So figure it out. Take the opportunity to learn something from this other writer. And add what you learn to your own toolbox. It just might come in handy.

5. Was there any deciding moment that prompted you to give the green light for a film adaptation of one of your books?

Alright, look. I like screenwriting. Lots of fiction writer friends I know also like screenwriting. Of course I was going to ask about this too, having the opportunity to speak to such great and acclaimed authors!

Especially since a healthy three out of five professors had a creative work of theirs adapted into a movie, and goodness knows getting on the big screen is just as mystical as publication.

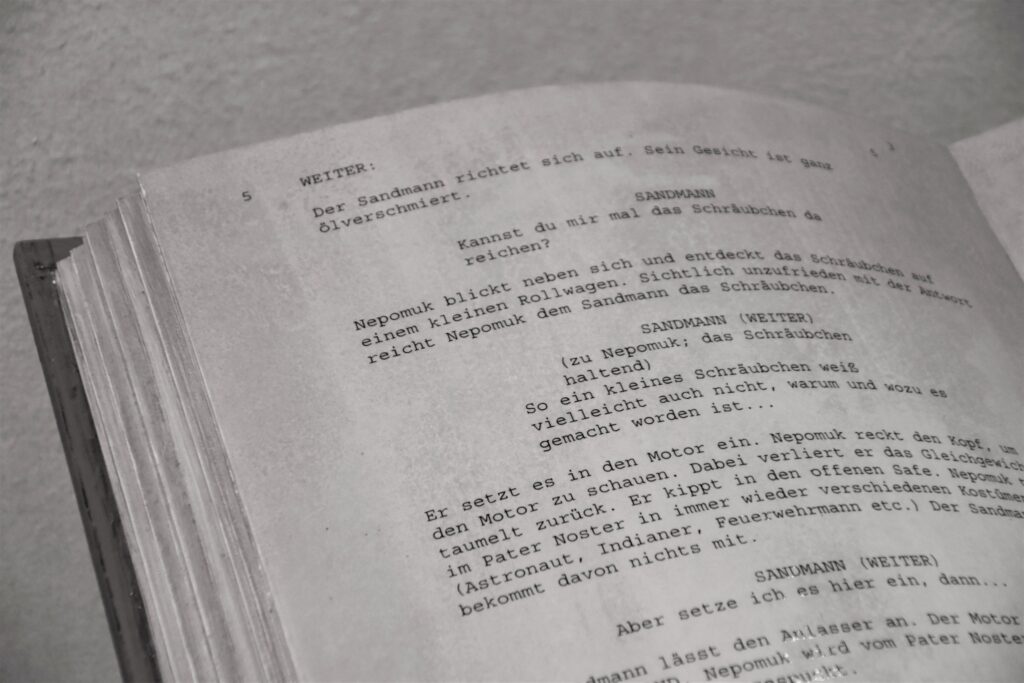

For D’Aguiar, his novel “The Longest Memory” was adapted. His insight goes: “I was in the UK, somebody read it and asked me about it. I had an agent who asked me about the writing of a script with the director. It came through, with the book getting good reviews, things like that. If it’s a good story, people tend to notice it. Once you have an agent, they usually have subsidiary rights. The agent’s house will have novels, televisions, drama, young adult–they cover everything in the house. So if you, say, write a young adult novel and the agent is waiting for an adult novel, they might pass it to somebody else in the house.

“So the experience is just luck. It’s good reviews that looks like it’s lending itself to other media.”

Simpson’s “Anywhere but Here” became a movie directed by Wayne Wang, starring both Susan Sarandon and Natalie Portman. Her answer: “I didn’t really have much to do with that, it’s more something the agent did. But I think now, with so many good television shows and independent movies with dimensional characters, there’s much more room for the kind of writers we nurture, so I think it’s a good time to go into those fields too.

“Of course it’s very different, and a lot of it comes down to whether you’d rather work collaboratively or whether you prefer to work alone in the room, and what do you want to really explore. Deep interiority will always be more possible in books.“

Jager’s “The Last Duel” became adapted into a film directed by Ridley Scott just last year. We talked about his process in researching and publishing the novel earlier in the first question, before interest in its film rights followed: “Actually, writers wait for the studio bosses to give the green light. But there was a moment when things clicked. In May 2019, I was invited to meet with Matt Damon and Ben Affleck and a couple of producers to discuss The Last Duel. Matt had a copy of my book filled with yellow post-it notes, which seemed like a good sign.

“As for me, I brought along a full-size steel reproduction of a medieval helmet. When I unwrapped it, Matt and Ben took turns trying it on and snapping photos. One of them texted a photo to Ridley Scott, who replied enthusiastically at once. I thought, This project is going forward!”

I don’t know about you, but the mental image of a full-sized medieval helmet getting passed around a table does wonders for me.

A huge thank you to these wonderful UCLA professors for taking the time to get interviewed by a hopelessly confused English major, and sharing some very helpful and insightful words on publication!