When I was five years old, my parents moved from Buenos Aires, Argentina to Miami, Florida. My image of America involved of Mickey Mouse and McDonald’s, so I didn’t expect moving here to come with so many hardships.

A few years ago, my dad told me that when he dropped me off for my first day of elementary school, he cried knowing he had left me in an unfamiliar environment. He was right, though—not a single person in my first grade classroom spoke Spanish. I remember my teacher giving me a word search puzzle that I couldn’t figure out. After I cried, they realized I was too young anyway for first grade. My teachers put me in an ESOL program and moved me back to kindergarten. Years later, even after the six-month program and years in school, I still speak with an accent and often pronounce words incorrectly.

If you’re a first generation immigrant like me, you understand that not everything came easy growing up in the United States. No one could help me with my reading homework in elementary school, since my parents were learning English themselves. No one could really help me when it came to making friends, as my parents were trying to make friends themselves. I now correct and edit my parents’ emails and paperwork. I’m their guide to the American system.

FSU junior Sara Gomez remembers finding the balance between fitting into American culture but holding on to her South American culture. “My parents grew up in a completely different environment in South America, so they never really emphasized American values in our household. My parents expected me to follow their footsteps and stay at home,” Gomez said. “It was a difficult process of explaining and understanding the fact that in order for me to attend a four-year university, one of the main reasons they immigrated here in the first place, I would have to leave home.”

In many cases, not only do we have to convince our parents, but then we also figure out the American university system on our own. “I had to learn about picking classes, financial aid, loans, interest rates, different insurances rates and their premiums. You name it, I had to figure everything out and how to pay for it. Even simple things like sending an email and knowing how to format it, revising an essay and even making a resume,” FSU senior Jeremy Kadoch said.

When I started applying to colleges, I planned my entire college tour by myself. My parents didn’t know how the system worked, so they never participated in Florida Prepaid and left it up to me to fill out my FASFA. “Where my family is from, people don’t move out of their parents’ house until they are married. Leaving home for college really isn’t common. Since I was the first of my siblings to leave home, I had to do a lot of convincing for that to happen,” said FSU junior Pam Vargas.

Regardless of their feelings about this new lifestyle, my parents still drove seven hours for parents’ weekend and sat through an entire football game Tomahawk Chopping, because that’s all they really understood.

A striking number of students said that growing up with immigrant parents taught them about sacrifice and hard work. According to a study by John Hopkins University, immigrant children who came to the U.S. before their teen years achieve higher in academics and school engagement than native-born children.

“I think about how successful my parents are and how much they’ve done for our family and it’s very humbling,” Vargas said. “They were not dealt an easy hand but have shown me that that means nothing if you are determined and willing enough to turn things around.”

Like Vargas, many immigrant children or the children of immigrants can see the sacrifices their parents made, and it affects their perspective on the college experience. “My parents often have a lot of expectations of what they want from myself and my brother because they worked their asses off to provide for us so we could do better for ourselves,” FSU senior Michelle Conde said. “We don’t really have a lot of money but they try their best to help me any way just because they know I’m doing exactly what I need to do to have a better life than them.”

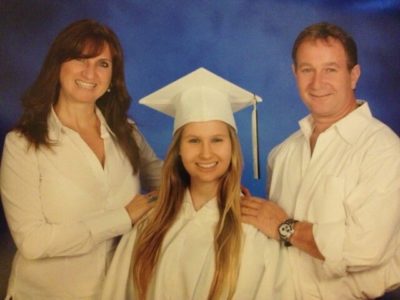

Before I graduate, I look back and realize how different my life would’ve been if my parents hadn’t made the decision to move to another country. My mother taught preschool at our synagogue in the U.S., allowing me to take Hebrew classes and visit Israel at 16 years old. I lobbied for Marco Rubio’s office in Washington D.C. to support The Dream Act, and now I’m about to receive a Bachelor’s degree from an amazing university.

My dad works many jobs, many of which involved him fixing floor tiles of houses at 50 years old. My dad, speaking broken English, remodeled a clothing store in Miami’s South Beach. My mother worked as a mental health counselor even though it took her 15 years to renew her license from Argentina. This summer, for the first time in 15 years of living in the U.S., my parents will go on their first true vacation to Washington D.C. Thanks to my parents, my brother went to law school and I earned my Bachelor’s degree.

Mami y Papi, I’ll carry your values in my heart and be proud to have immigrant parents for all of my life, because no one knows how to value success more than those who worked so hard for it.

Gracias Mami y Papi, no hay suficiente “gracias” y “te quiero’s” por lo agradecida que estoy por la vida que me dieron. Aunque estoy un poco Americanizada, me llevo siempre conmigo tus valores, el valor de trabajar duro para lo que alguien quiere. No tengo la menor idea que voy hacer ahora que soy adulta, pero ustedes me enseñaron que a veces hay que escuchar a su corazón y si nunca ustedes escucharon a su intuición nunca estaríamos acá celebrando mi recibimiento de la universidad. Por el resto de mi vida voy a escuchar a mi corazón.

Los queiro y este diploma se los dedico a ustedes,

Sharon