Not all athletes are born equal. I can attest that as a diver on my varsity swimming and diving team. Weird, right? You probably associate athleticism with the jock stereotype you see in every teenage movie ever made and with automatic popularity. But have you ever paused to break down what entitles one to that honorable title of jock? Football players are the obvious choice, soccer (She’s the Man) and hockey (The Mighty Ducks) come in at a close second. Recently, a swimmer was the social top dog of the Netflix Original Sex Education. I was really excited to see that because that’s my niche.

Diversity of sports representation in media definitely doesn’t make headlines. Should it?

In high school, my swim team won the regional championship for 13 years in a row by the time I made it to senior year. The football team, on the other hand, could barely pull off a win once a season. Apparently oblivious to this, our school funded enormous banners of each starting football player that hung from the bleachers at our field. Even their letterman jackets looked cooler than ours, with leather sleeves compared with every other sport’s standard cotton jackets.

I felt particularly proud of my letterman jacket because I accumulated nine different pins in my career, marking various athletic achievements. The football guys and their fancy jackets completely undermind this pride. They literally strut down the hallways in packs: crotch leading the way, arms stiff and shoulders waddling with each step to make room for all of the make-believe muscles. We’ve all seen it.

I also wondered whether the players seemed so cocky because the administration treated them like they were really worth something, or the other way around. My guess, and the source of my frustration, is that these guys were conditioned to hold their heads a little higher than everybody else. Their funding was through the roof, while we needed to fundraise like crazy and fight neighboring towns to tie down practice slots at the local pool.

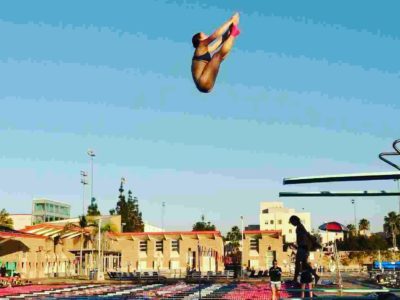

Even within my own team, I felt marginalized, and this bothered me equally as much. The team included about 40 swimmers and only four divers. We took up two out of the six lanes in the pool twice a week when our practices overlapped. During meets, diving took about half an hour of the three-hour meets.

Not only was I new to diving in high school, but I was also new to around others swimming so closely. I supported my teammates and learn about both sports as much as I could. The divers spent the meets at the end of the lanes, losing our voices screaming at the swimmers to go faster and out-do the girls next to them, just like their fellow swimmers.

During the “diving break,” the swimmers did a synchronized clap before each dive, giving the illusion of support and interest. Some of the girls seemed genuinely dazzled by the diving. But it was completely clear that the majority of the team attempted to subtly check their phones, giggle with the girl next to them or even take a power nap. This always hurt me.

It felt like our sport was a helping hand to the larger team goal.

This was fine, but the work we put in every day wasn’t fully appreciated.

This didn’t change when I got to college, either. In every team speech, the coach tagged diving onto sentences about swimming as an inclusive afterthought. This alienated swimmers from the hard work the divers put in. It also made me feel like what was being said to the whole team didn’t apply to me.

Once again, diving breaks plagued by the swimmers’ and audience members’ chit-chat and Instagram. One of my best friends on the team had his back turned the first time I competed with a new dive that I told him I was excited about. Meanwhile, my fellow divers danced on deck in celebration of my accomplishment. There is inevitably a stronger athletic bond between those who train and compete the same sport. I craved for my swimming teammates to ask questions, be observant and basically give a damn about what I was doing.

My head coach really did care about fusing this disconnect, but I still felt like I couldn’t discuss my sport with him because he wouldn’t understand what I was talking about very well. Ultimately, I was a minority on my team and was treated as such.

Socially on campus, sports teams drive the party scene and the general categorization of people into friend groups and labels. Each team has its own reputation. Hockey players are too old to be in college. Lacrosse players run the underground fraternities. Rugby women are aggressive feminists. The field hockey team is rich, white and blonde. Golf players are Republican. Skiers party hard. These are all assumptions that play an active role in the making of or preventing friendships on my campus. They dictate what you expect from someone and how you treat them. I found personally these quite isolating and exclusive. People naturally filter into friend groups based on sports team out of convenience and comfort.

One of my friends said, “If my friend on the crew team is sitting in the dining hall with only his teammates, I’m not going to go and sit with him.” Why? That seems like the perfect opportunity to make a whole new group of friends. He even has an in! But very real social barriers prevent this type of interaction and understanding between students on a college campus.

Overall, sports teams create not only a hierarchy, but also a series of social islands that are inaccessible to most. My position as a minority on a team not particularly high on the social ladder made this all the more obvious to me.

To be clear, this is by no means a complaint about being oppressed. Athletics are just an activity, not an identity or a career for most. But I do think that noticing moments of unjust hierarchy or exclusion in other pockets of life can be a useful entry point into tackling a much larger host of issues facing our society, especially for those who feel unable to directly empathize.

It is clear that there is a discrepancy between the social status of male athletes and female athletes. But there is also a cultural hierarchy of sports that creates a barrier between individual people. With genuine curiosity and respect, I believe that can be fixed—but it’ll take a village.