“I’m Cuban.”

“Oh, cool. When did you come to America?”

In Miami whenever you’d say where you were from, it was assumed your parents were the immigrants. When I went off to college, for the first time in my life, I had to explain how even though I wasn’t born in Cuba, that didn’t mean I wasn’t Cuban.

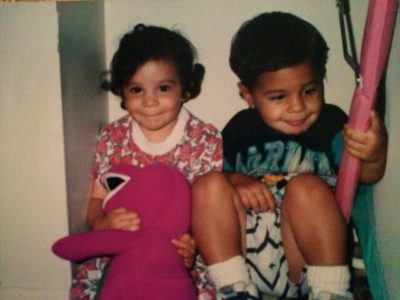

I was born and raised in Miami, Fla.—home to one of the largest Cuban communities in America. Cortaditos, pastelitos and Celia Cruz raised me— along with my Cuban family, of course.

My family left Cuba in the early 1960s after their homeland fell into the hands of a dictatorship. During this first wave of Cuban immigrants, the American government did little to help these refugees. From an early age, I knew of the hardships my grandparents and my parents had faced in their search for a better life for their children.

Growing up, I never questioned what my heritage was. I was Cuban but born in America. I never had to explain that to anyone in Miami because we were all on the same boat. I had not fully acknowledged the fusion of these two very different cultures in me until a few years ago.

My first class at the University of Florida was the first time I was surrounded by so many Americans (I’m talking great-grandparents-were born-here Americans).

Their lingo was different, the way they dressed was different—even the way they greeted each other was different. In Miami, we greet each other with a kiss on the cheek. The first (and last) time I tried to do that in Gainesville I had to explain to that person that I was not trying to make-out with them.

My Spanglish didn’t roll very well here either. It would not be a stretch to say that Spanglish is basically the non-official second language of South Florida and brings with it a lifestyle. Saying ‘iregardless’ and ‘like’ after every word and eating croquetas on the daily is a little taste of what our lifestyle is like. Some of my new college friends had no clue what I was trying to say at times since there isn’t always a direct translation from Spanish to English (apparently, ‘eating s***’ is not what Americans refer to as ‘not paying attention’).

The more I thought about it though, despite growing up in a predominantly Cuban environment, attending the University of Florida and living in Gainesville unveiled to me just how much of American culture was engrained in me as well. While Noche Buena (Christmas Eve for Cubans) wasn’t Noche Buena without a massive roasted pig, fourth of July wasn’t complete without the sky igniting in red, white and blue fireworks.

I have a huge interest in American politics and make sure my voice is heard by voting, but Cuban politics are just as important to me. I cry along with the rest of America when tragedy strikes, and I also shed tears for the country my family used to call home.

There are bits of both cultures mixed into my life, and that leaves me in a gray area along with other first-generation Americans who don’t know exactly what bubble to fill on a scantron when asked about their background.

Luckily, I’m not the only one.

I have met students here at UF that experience the same confusion I’ve experienced. It’s also refreshing to hear my other Miami-born friends talk about their struggle to adapt to hand-shaking over kissing.

I’m not sure if we’ll ever fully identity to one particular culture over the other, but this college town has shown me that that’s OK. Living in Gainesville has taught me so much about American culture, and at the same time it’s taught me to embrace my own.

I am Cuban-American.