When we get our college acceptance letters in our senior year of high school, we usually don’t think about our chances of the stress triggering a mental illness. On top of that, the thought of our university threatening to take away our right to an education because of a mental case never crosses our minds. Unfortunately, this was the case for Pooja Mehta. She left to attend a prestigious university, already experiencing a mental illness. Although she hid her symptoms for a while, she eventually had a panic attack. The friend she called in the moment of crisis reported her to the administration. The school, concerned something might happen to a student on their campus, told her she needed to take a leave of absence. This led her to fight for her education and start what is now the largest organization at the University: NAMI on Campus.

Read on to learn more about Pooja’s story and how you might start a NAMI on Campus at your school.

Q: Did you feel more pressure to hide your mental illness because you went to such a well-known, prestigious institution rather than a smaller, lesser-known university?

PM: I don’t think so… I didn’t attend another university, so I’m not entirely sure what my experience would have been at another school. But I think for me, it was more of a continuation. I got diagnosed when I was 15, and I hadn’t told anyone outside of my immediate family for the three years that I was in high school with my diagnosis, and so when I went to college, it was more of a continuation of that. It wasn’t initially anything about the school that made me want to or not to be open about this. It’s just kind of like that was the status quo of my life up until that point, and I just kept it going.

Q: Why do you think the university immediately decided that you were dangerous after your panic attack rather than offer you counseling?

PM: I don’t know. I’m going to be honest. This experience happened when I was 18 years old. So that’s 10 years ago. And it was a very emotional and very stressful experience.

And so I can’t speak to what the university was thinking, but I mean the university, the people that I was meeting with and having these conversations with; their best interest was the school. I think it was a combination of ignorance of what mental health conditions are and what mental health supports look like as well… Just to kind of put it bluntly— they didn’t want to risk a student hurting themselves or attempting suicide or completing suicide on their campus and so I think [that’s what] I’m speculating what was happening from an administrative perspective. They’re hearing that a student is struggling, and they’re immediately thinking, “What can I do to best protect the university?”

Q: Did the university offer any counseling services or mental health supports at the time?

PM: There were. So, the Counseling and Psychiatric Services were available. Actually, it was something that I enjoyed a little bit, and for what it’s worth, the providers I was able to talk to at Counseling and Psychiatric Services on [my university]’s campus were wonderful. And they continued to build on that program. But at the time, I did see a provider, but because of my situation, because of my circumstances, I was only able to get one or two appointments. Even then, when I called, there was a pretty substantial wait time to be able to see the provider. It just wasn’t set up to be a sustainable option, and I don’t know if that’s changed since. I hope it has.

Q: How did you find out about NAMI on Campus? What intrigued you about the idea?

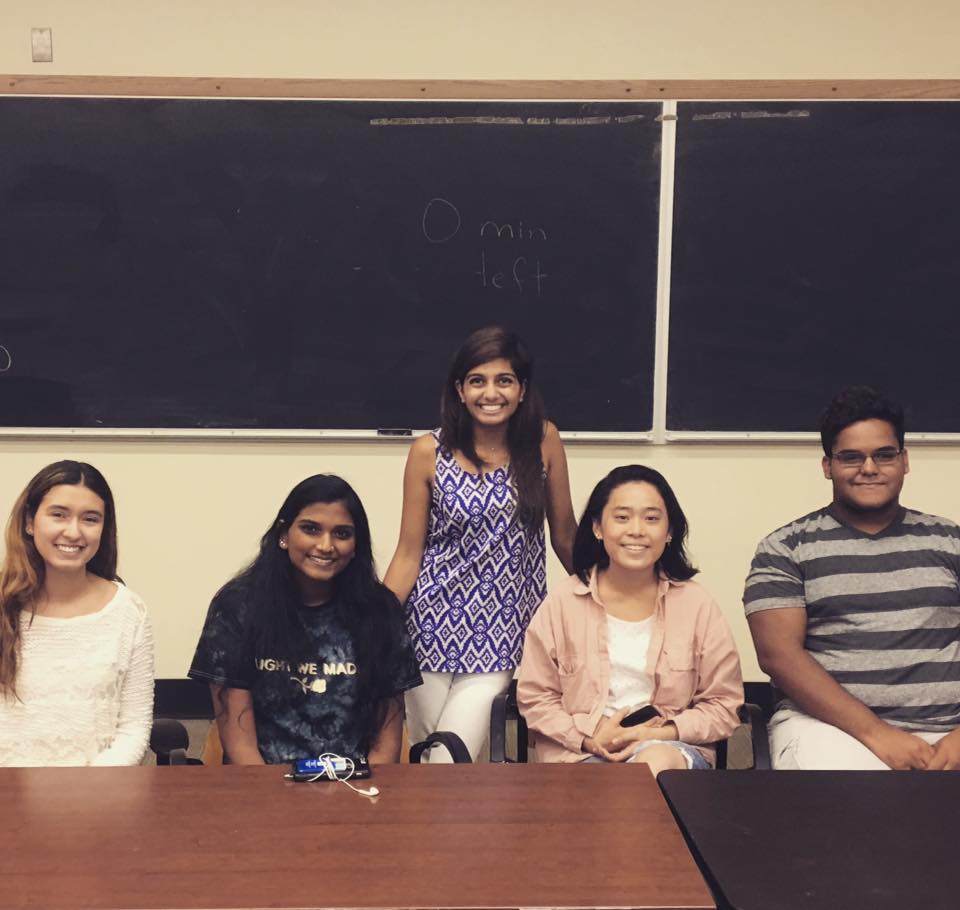

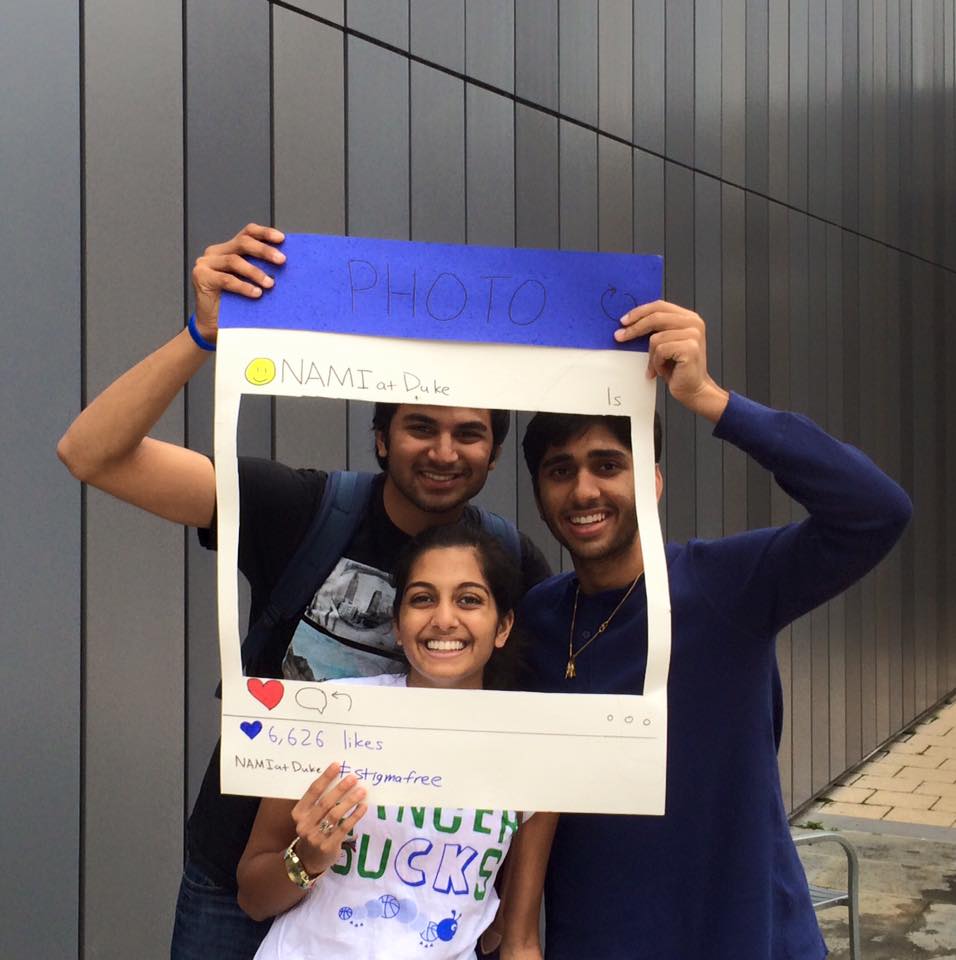

PM: So, there was another student, actually, who posted a community page about how he was struggling and how he wanted to start this organization, and I immediately messaged him. We went to go talk to our local NAMI affiliate, and they connected us with the State office, who helped us get set up with a NAMI on Campus, and we got it established. We created our own little charter, constitution. I forget what it’s called within the parameters of the University. And so that was the beginning of my junior year. And it’s still going. It’s still running. And from my understanding, it’s doing really well.

Q: Can you give students a brief summary of the benefits of having a NAMI on Campus?

PM: Because we understand that the dynamics of different schools and the needs of different student populations vary, we give student leaders a lot of leeway to make it what works best for them. I think the only caveat that we really emphasize is that you can’t provide clinical care because you’re not qualified to. But those are the basic parameters that we put in every group.

Beyond that, I know some NAMI on Campuses really, really focus on the community and self-care. Having community events, where pizza parties or movie watch nights or ways that you can just connect with your fellow students and kind of combat that feeling of loneliness and isolation in a way that’s a little bit less overwhelming than going to a party, or a fraternity event or something like that.

Others focus more on the one-on-one connection of having a mentor system and facilitating events where people can do things as pairs and kind of build up more close relationships. One of the things that we did at [my university], which I really think was so valuable, was we had a buddy system, where, if you are going to CAPS (Counseling and Psychiatric Services), and you don’t want to go alone, or you are worried, or you are scared, or you just needed someone to go with you, you could sign up, and someone would go. I sat in the waiting room, and I was there when they came out, and we went to go get frozen yogurt, and I think that helped them get over that fear of going into their first appointment and doing this for the first time.

Q: What is your favorite thing about NAMI on Campus?

PM: So, after my [panic attack, I was] so frustrated because, basically, their conclusion was, “You need to take the rest of the semester off. You need to take a leave of absence.” After negotiating the terms under which I could stay on campus and complete the semester, I wrote an article in the school newspaper anonymously [that said] this is what I’m going through. Because, on the surface of it, I’m a “normal” person. I have a lot of friends. I was in a sorority. I was not one of the “popular” girls, but people knew me. People hung out with me. I was involved with clubs, and I was a normal person, student or whatever, and people had no idea that I had just spent the last 48 hours literally fighting for my right for an education.

And so starting the NAMI on Campus was the first time that people had a chance, including me, to openly talk about these issues. The first time I ever told my story on my own terms with my name attached to it was the very first, not only on campus panel, at [my university], and not only was that such a turning point in the conversation around mental health on campus it was also a big turning point in how I viewed my mental health issues. It was no longer this dark secret, this thing, to be ashamed of and to hide. Not only is this something that can provide help and connection to other people, but it’s something that I need to acknowledge within myself and I need to deal with in myself. And it’s okay that I do, that it doesn’t take away from everything else that I am.

Q: Can you offer any advice to students who may be in a similar situation to what you are in?

PM: My advice would be to speak up, but I know how difficult it is to do that. I think one of the things that we talk a lot about NAMI and in the advocacy space is the power of telling your story… I wish I had better advice beyond that because once I started telling my story, my life took a full 180 for the better, and yes, there was some backlash. Yes, there was some stigma, and some pretty iffy things have happened in the aftermath of it, and again. But every single time something bad has happened because of people knowing about my mental illnesses, it is not because of my mental illness. It is a because of a lack of their understanding of what it is and or a fear of liability or safety, which is quite unfounded.

Q: Is there anything you would like to add?

PM: I think being able to have a place on campus that is a designated stigma-free zone is really important. That’s something that we talked about a lot in the establishment of our NAMI on Campus, because [my university] is a very prestigious and high-achieving university. But it’s something that I suspect happens on every campus. [There is] what I call the Swimming Duck Syndrome, where you see all these ducks on the water, and they look like they’re just kind of gliding along and living their best lives. You’re not seeing how frantically they’re paddling under the water. And the faster the duck moves on top of the water, the more effort and more strain it’s taking underneath, and there is a certain point where the duck needs to stop moving, or it will get tired, it will get sick. It will get hurt. And I think having places where you can take that pause where you can acknowledge how hard it is to paddle sometimes, where you can be honest about some of the things that you’re struggling with, I think having designated spaces to talk about that stuff, especially spaces that aren’t comparative.