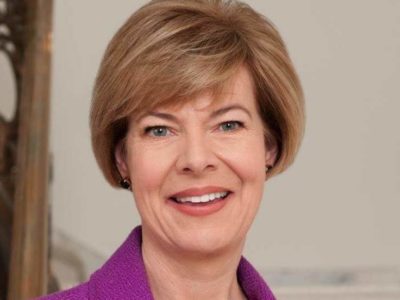

Tammy Baldwin has been working on a progressive agenda all her life. Though she’s currently our liberal champion in the Senate, her inspiration for political action started during her middle school years. This passion stuck with her all through college and drove her to run for her local county board shortly after her undergrad. Pushing for the rights of the people and listening to the locals got her elected first as a representative, and then as a senator from Wisconsin who is working to ensure that all people maintain their rights in these challenging times.

Senator Tammy Baldwin Career Timeline

1984 – Graduated with a B.A. in mathematics and government from Smith College

1986 – Elected to the Dane County Board of Supervisors

1989 – Graduated with a J.D. from the University of Wisconsin Law

1992 – Elected to the Wisconsin Assembly

1998 – Elected as a U.S. representative from Wisconsin

2013 – Assumed office as the junior U.S. senator from Wisconsin

Q&A with Powerful Women Leader Senator Tammy Baldwin

Q: At College Magazine we’re working together with EMILY’s List, Emerge America, Human Rights Campaign, Higher Heights, She Should Run, Victory Fund and IGNITE on an initiative to fight for equal representation in congress called “50 by 2050.” What are your thoughts on the goal of achieving 50% of women in Congress by 2050?

A: I think it’s a fabulous goal. I hope all sorts of folks are thinking about that in other respects too—50% of corporate CEOs, 50% of nonprofit CEOs, 50% of the leadership of all sorts of organizations in all sorts of arenas. But, I sure think getting 50% of congress composed of women by 2050 is just a fabulous goal.

Q: What inspired you to run for public office?

A: The first I ever thought about public service, literally, was in middle school. I had a chance to serve on our middle school student council. There I was a really young woman, a young girl actually, and I felt what it feels like when you make a difference. I had worked on some small, local projects. I actually worked on an international project and I remember how it felt to know that my work made somebody else’s life better. I also remember how it felt to realize I wasn’t too young to make a difference, even though I was far from adulthood or the ability to vote or whatever. That was my first taste of, “Wow, this feels rewarding. It feels purposeful. And I’m not too young or insignificant to make a difference.” Or maybe the opposite way of saying that is, “Wow, I can have power even though I’m in eighth grade—power to make change.”

Q: At College Magazine, we’re the guide to the undergraduate experience. In what ways did your experience at Smith College and the University of Wisconsin help prepare you for your experiences in public service?

A: First of all, let me pick on the obvious one, I studied government in Smith. I had a double degree, mathematics and government. The math wasn’t for a fallback career, by the way, I just liked it. So I was studying government. I was also involved in some political causes. I was really interested in the effort to pass, this was sort of the final days of the effort to pass the Equal Rights Amendment. There was also the early LGBT civil rights movement. It was still fledgling in many ways in the middle 1980’s. We were far from where we are today. Between what I was studying at Smith and the exposure to organizing, I got really excited about it.

Then I moved home to Madison, Wisconsin, just for personal background, my grandparents raised me. And my grandfather had passed away between my junior and senior year in college. It was really important for me to get home to Madison to help be there for my grandmother, who lived many, many years beyond that, but I think of the responsibilities that women disproportionately take on, and caregiving for relatives is one of them. Just to share one more thought about my grandmother, I know I’m going on a tangent—she was born before women had the right to vote, she was born in 1906, and she lived until 2001 and she had the opportunity to vote for her granddaughter to become a member of the United States Congress in 1998. There’s just something to me so poetic about the changes she saw.

So that was a big factor too, but you were asking, Smith College, and then moved back home, took a year off before law school, volunteered on every campaign I could get, just every progressive candidate. I wanted to take what I had learned in the textbook and find out what it meant on the street. By the next year, by my first year in law school I was running for office.

Q: How did you get started? How did you develop a platform on which to run a campaign and gather the support you needed to run?

A: To the latter question, gathering the support I needed to run, had a lot to do with that gap year between college and law school. As I said I volunteered on everyone’s campaign—three or four city council races, a bunch of school board races. There was a major referendum that was put on the ballot that would have cut back local services, police services, fire services, social work, what have you, it would’ve cut back. So I started working with the local labor unions for public employees to fight against that referendum, and we actually won. This was supposed to be a property tax freeze or cut, and people said, “No, these services are too important to who we are as a community.” I showed up, and I networked, and when I found out that my county board supervisor was retiring and I had an opportunity to run, I went to everyone I had helped and done doors with for other people and said, “Hey, can we do them together for me now?” And mostly I got yeses. It was rolling up my sleeves, getting involved, person to person work.

There were a couple of issues that I felt completely passionate about. You already heard one of them, which is participation in the LGBT civil rights movement and equal rights. Another was healthcare. The reason is because, when I was raised by my grandparents, I had a serious childhood illness. After I was hospitalized for three months and then totally recovered, my grandparents couldn’t get health insurance for me because I had a preexisting condition. I had been ill before, that’s what they mean by a preexisting medical condition.

As I learned about this as I grew older, I felt it was so wrong. At the time I was running for the county board, the county was in charge of a healthcare program for poor people, yet they said that university students were not eligible for this because they were poor by choice, college students were poor by choice. I kept encountering people who were in positions like I was when I was a child, they had no insurance, an illness, they became ill, and there was no source of help. Anyway, that’s a long-winded way of saying I ran for the county board to work on healthcare for all and civil rights injustice.

And the other thing I would’ve mentioned that actually brought these two battles together—I was elected to the Dane County board right at the beginning of the HIV/AIDS crisis in this country. People were also being discriminated against in the healthcare system. People were being excluded by basis of their HIV status from public activities. It was an opportunity for me to emerge as a major leader in both of those movements. It basically sent me the same message back when I was a middle schooler, which was, “I’m not too young to make a difference.”

Q: Were there any specific challenges that you faced as a woman running for office?

A: Yes, but I would say about some of the challenges facing me, I want to say I faced more age discrimination as a very, very young person who was elected to a board where most of the colleagues were old enough to be my grandparents, and getting them to take me seriously, and my very youthful constituency to take me seriously—I ran for the county board seat that represented the university campus. We actually had a fair number of women on the Dane County board, my first office, but I was a stand out in terms of being 24 years old when I was sworn in, and most of were 60s, 70s, for the most part.

When I ran for the state legislature, I ran in 1992, and that was, “The Year of the Woman in Politics.” It was the year that Anita Hill was grilled by the all-male senate judiciary committee about being sexually harassed. All of these women looked at that and said, “Oh, these guys do not get it,” and started running for office. It was something very similar to what we’re seeing right now in Trump-world, where people are looking at this president and what he said during the campaign and what he’s doing now and saying, “We have to amplify our voices. We have to be heard. We have to run.”

In any event, I ran for the state legislature in 1992, and the thing I had to be vigilant about all the time was reporters who were saying, “What is your women’s agenda?”—as though I wasn’t running for an office to represent everybody. You know, you’re running in the year of the woman so this must be all about women’s issues.

Q: In the last few months in particular, we have been seeing a lot more women running for office. How do you feel that will end up shaping our political landscape?

A: The more progress we make towards 50 by 2050, the more that women’s voices and life experiences will shape the policy of our country, of our states, of our communities. There’s a young woman who is a state representative for downtown Madison, Wisconsin, her name is Chris Taylor, and she talked to me about whether she should run for the state assembly back when she launched her first campaign. She said, “I’m really worried, I have young children and I’m worried, with children that young, should I be running for office?” And I said, “Chris, policy on children, childcare, parental leave, etc. is made by people who do not share your experience. It will not be the right policy. We need your voice there.”

And she ran, and she won, and she tells that story all the time because that’s what happens, you bring your voice to the table—your voice conveys your life experience. If you’ve experienced sexual harassment, sexual assault, domestic violence, if you’ve been held back in getting ahead because of gender issues, if you worry about whether we will have access to our full constitutional rights and full reproductive care, our voices matter and should shape the debate.

When Donald Trump signed his first executive order relating to issues of reproductive choice, and it was basically the global gag rule, it was another photo of all white men signing an order relating to women’s bodies. How many times have we seen this image? How many times?

Q: For college women who are interested in going into elected office, can you describe what a day in the life of a senator is like?

A: Days in the life of a senator, there’s no such thing as an average day. I go back and forth every week between Wisconsin and Washington D.C. and the tempo and flow of things are different depending on which city I’m in. So I’m in D.C. when the senate’s in session. My days include lots of Wisconsin visitors who fly out to D.C. to talk about issues that they’re passionate about. It entails committee meetings and I’m on several different interesting committees, important committees. It involves important debates on the floor of the senate and casting votes. It involves giving speeches to groups that are assembling in D.C. to rally for change that I support, that sort of thing. That’s the type of texture of my D.C. days.

When I’m in Wisconsin, it’s really to listen and to solicit input on issues that are important to the people I represent and that I’m working on. My constituents help keep me informed about what they’re feeling, what they’re anxious about, what they’re hopeful about. So it’s a lot of traveling the state, and it’s a big state, so there’s a fair amount of car time.

While D.C. is meeting every fifteen minutes, Wisconsin is more: take a tour at a manufacturing site, jump in the car, drive 45 minutes, have a roundtable on opioid and heroin addiction and treatment to hear from constituents about how the epidemic is facing our state, get in the car again, have a roundtable on student debt and talk about my measure to help people eliminate student debt from their future but also to hear their stories about how they’re grappling with it, and then get in the car again and drive to meet with small business entrepreneurs that are going to take the risk of their life and start a new business. So that gives you a flavor of what happens in the different places.

My county board experience was different and much more local. All politics is local and I really do think local politics is a great place to start. You can see the difference you’re making in your community right before your very nose.

How to Become a Powerful Woman Leader

1. Participate

“Working on other people’s campaigns was enormously helpful to me to learn how to run myself. The other thing is, there are so many organizations out there that I am a huge fan of that provide training. Study politics. Study campaigns and elections.”

2. Practice Your Skills

“Ok, so you have to raise money. Let’s practice that. Ok, you have to do television interviews. Let’s practice that. It doesn’t necessarily come naturally. It’s really, really valuable to practice,” said Baldwin.

How to Connect with Senator Tammy Baldwin

Write her a letter or give her a call:

MADISON

30 West Mifflin Street, Suite 700

Madison, WI 53703

Phone: (608) 264-5338

WASHINGTON, D.C.

709 Hart Senate Office Building

Washington, D.C. 20510

Phone: (202) 224-5653