There exist a few defining features of English classics in our collective consciousness: long-winded sentences, archaic customs and a level of difficulty that wears down your patience. As a bright intellectual of the 21st century, you feel compelled to follow in the footsteps of your predecessors and prove your worth by cracking open Jane Eyre. But ten pages in, your focus wavers and you find your eyes wandering in search for something a little less…“English.” Don’t worry, been there and done that. The solution to your problem actually lies right before your eyes: translated literature. While you can still read these books within a language you fully understand, they offer a completely different set of storytelling methods and cultural understandings that can broaden your mindset.

If you feel ready to leave behind the English canon, come dive into a whole new world of literature with these 10 classic books in translation.

1. The Little Prince by Antoine du Saint-Exupéry (translated by Richard Howard)

What better way to make your first foray into translated literature than with a children’s book? Deceptively simple but ripe with meaningful symbolism, The Little Prince actually speaks to neither children nor adults but to the children embedded deep within the hearts of all adults. A pilot who crash-lands onto the Sahara Desert narrates the true-hearted Little Prince’s tale travelling across planets and encountering cynical and self-absorbed adults and faithful friends. As you follow along the Little Prince’s journey, you will come to rediscover the beautiful everyday things people tend to neglect as they grow older and society subsumes their individual imaginations. With short chapters and seemingly random plot points, the story evokes a sense of childish wonder that never fails to tug on heartstrings. It comes as no surprise then that The Little Prince sits among one of the most translated books in the world, truly embodying the spirit of translation in its ability to resonate with readers of all origins, ages and languages.

2. The Stranger by Albert Camus (translated by Stuart Gilbert)

Camus’ The Stranger similarly packs a heavy punch with simple prose and an initially indecipherable storyline. Set in French Algeria, the book follows the unorthodox Meursault, a man who begins his story by showing a great amount of aloofness for having just lost his mother. Throughout the book, you’ll find yourself trying to pick out a sliver of rhyme or reason in Meursault’s actions but ultimately fail, just as the people around Meursault do. All of this falls within Camus’ intentions, however, as the book presents the absurdity and meaninglessness of life as its primary philosophy. Weaved within its presentation of philosophy, The Stranger’s depiction of racial dynamics in French Algeria also offers a glimpse into colonial entanglements within the bounds of the colony rather than as an ignored sidenote in the periphery of many traditional English novels. Though the book’s narrative focus still belongs to the white French, white and Arab characters inhabit the same physical space, making a look into the troubled hierarchies within the colonial society unavoidable. For those who much prefer untangling dense philosophical concepts without added extravagant, wandering prose should definitely look to The Stranger for a challenge.

3. One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez (translated by Gregory Rabassa)

A fan of Toni Morrison’s ghost-ridden Beloved? Check out One Hundred Years of Solitude. The first book of Nobel Prize-winning author Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude pioneered the genre of magical realism, in which aspects of the supernatural present as a part of mundane life. Over the course of a century, the story paints a portrait of the seven generations of the Buendía family and Macondo, a made-up town in Colombia discovered and established by the head of the Buendía family. As the isolated town makes contact with the industrialized outside world, war and chaos ensue, eventually leading to the fall and decimation of the Buendía family. The elements of magical realism penetrate the boundary between reality and absurdity, thereby merging our perceptions of truth and materiality. This becomes particularly interesting when considered in relation to the actual history of Colombia within the story’s time period. During a time of civil wars, colonialism and severe political instability, how does one navigate notions of reality amidst the absurdity of life? That’s for you to find out.

4. Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami

Another master of magical realism, Murakami’s vision captured the international literary sphere since his debut. His collection of works often explores the spectrum of human conditions through fantastical, dream-like scenarios, opting to capture the unspoken or elusive through manifestations of the supernatural. Depicting the journey of Kafka, a boy trying to escape a prophecy detailing his oedipal downfall, Kafka on the Shore perfectly represents this style. With talking cats and raining fish, the story baffles but compels you to reconsider how you conceive of the space between your conscious and subconscious realities. Murakami rarely gives easy answers, or answers anything at all. And this quality of magical realism—uncertainty—perhaps underlies the popularity of the genre among translated works and its readers. In each case, the reader gets to learn more about an individual, a community or a culture by their reactions to supposedly absurd events, gaining a broader view of the world as a whole.

5. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volonhonsky)

As you read on, you may find that a common but perhaps unexpected thread among many of these translated classics includes the universality of their themes. Despite the variety of physical settings and the unique cultural and historical understandings that inform each book, all of their investigations into humanity illuminate something fundamental within us. Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment comes as no exception. The book starts off with a moral quandary: do justifiable crimes exist? Following the perspective of the intelligent main character Rodion Raskolnikov after he murders a pawn shop owner for money, the novel considers the psychological effects of crime under poverty and the philosophical inclinations people take to justify their actions. Dostoevsky’s writing connects heavily with his experience becoming imprisoned and disillusioned and the state of affairs in 19th century St. Petersburg, Russia. The link to such historical context prompts you to reconcile with how you may conceive of crime, punishment and ideology within your own milieu, proving that the best translated books not only introduce you to unfamiliar worlds and cultures but make you reflect upon your own and examine it in a different light.

6. Old Indian Legends by Zitkala-Ša

Breaking from the mould of what we typically consider translated literature, Old Indian Legends features a collection of traditional Sioux legends and tales retold in English by Zitkala-Ša. The collection exists in preservation of Indigenous stories, then considered a dying culture by the general public under settler colonialism’ forced assimilation. Whether they illustrate the spider trickster spirit Iktomi or little animals of the prairie, each of the short tales delights upon the first read. But by the second or third read, you might begin to notice the subtle lessons emerging from the actions and relationship dynamics between the traditional characters. More often than not, the characters and their circumstances act as symbols that reflect and impart lessons crucial to life in Indigenous Dakotan communities.

“Her work made the fact of the indigenous language visible, that’s an anti-colonial gesture,” UC Berekeley Professor Beth Piatote said. Piatote teaches form and invention in Native American literature. “Otherwise, you would think those cultures were without language. Making those languages visible is an important aspect to share.”

Ša’s whimsical and lively prose makes visceral the setting of the Great Plains in the stories. She draws you into the world of the Dakota people in a way that, if executed poorly, may only come off as amusing little stories, swiftly forgotten. But the engaging quality of her writing and the inherently enduring life lessons the traditional stories impart compel you to pay attention. Ša’s work in delivering these tales in English reminds us that the core element of translation comes down to understanding and accessibility. In presenting her culture out to English readers, Ša forces colonial society to recognize the existence of her people.

7. Les Misérables by Victor Hugo (translated by Lee Fahnestock, et al.)

Adapted into one of the world’s biggest movies and musicals, Les Misérables details the events leading up to the June Rebellion in Paris in 1832. Centering on the story of ex-convict Jean Valjean as he attempts to repent for his sins, Les Misérables addresses a myriad of social problems through the experiences of its characters. Through the careful interweaving of its subplots and character interactions, Hugo presents man’s possibility for both progression and degradation under a society that exploits its laborers and doesn’t value cultivating those it left behind. Does belonging to a noble family guarantee goodness? And does breaking the law, any law, suggest depravity? Alongside learning French history, a read through this truly enormous book will grant you the opportunity to engage with conceptions of the social contract and where love and compassion fall within a ruthless society.

8. The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa (translated by Stephen Snyder)

A surprising spin on the stereotypical Western dystopian story, The Memory Police offers no satisfaction of a grand revolution or society’s attainment of justice and freedom. You might question what value a story like that holds, but trust me, the point of the story comes precisely from this sense of unresolvedness. Set on an unnamed Japanese island where a police force enforces various items to disappear from its residents’ memories, The Memory Police explores themes of loss and dispossession in a situation where one cannot possibly avoid them. Using beautifully simple language and striking, delicate images, Ogawa constructs the complex emotional landscape of people living under an oppressive authoritarian state. Pain permeates the losses in memory the characters experience, and yet beauty and intimacy persist within moments of connection. As you witness the main character’s misery in losing the memory of the things she holds dear, you’ll come to understand that the plot point of a revolution would stifle the book’s meaning, and a bit more about what it means to change under the pressure of a dwindling sense of self.

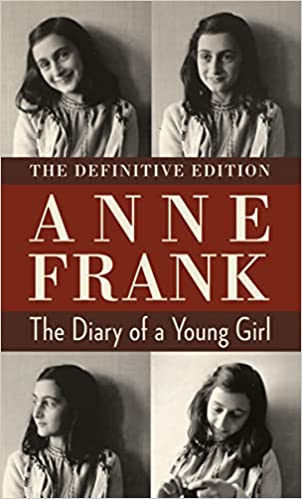

9. The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank (translated by Susan Massotty)

The inspiration for The Memory Police, The Diary of a Young Girl remains one of our most cherished pieces of literature. Written by a young Jewish girl named Anne Frank during the Second World War, this personal diary details life within the enclosure of the “Secret Annex” where Frank and her family lived in hiding from the Nazis. Beyond the fact that the diary documents the mental and emotional landscapes of select Jews during the Holocaust, it also most poignantly reflects to its readers the soul and personhood of its author. Even as deeply unpleasant and harrowing news of the war comes through, Frank’s words still maintain a jovial, animated tone. And despite the fact that Frank herself expressed a desire to write and publish a book, one cannot help but question the ethics of unveiling this private diary to the world. We must thus remember that, as a diary, the text does not function as fiction. We must treat it with the utmost respect, care and empathy as its author and the history she documents demand.

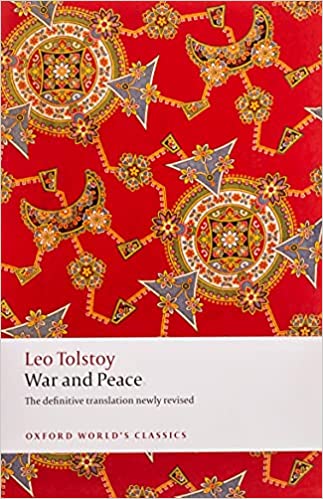

10. War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (translated by Louise Maude and Aylmer Maude)

Any good list wraps up with a bang and any good book challenges its readers. I challenge you to War and Peace, a book perhaps more known for its sheer length than anything else. Setting the scene with anxieties of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, Tolstoy mixes the narratives of Russians from a multitude of classes and backgrounds to render a complex work dealing with virtually every theme imaginable. Questions about the impacts of war, the facets of love and the motivations behind wealth find themselves in every part of the book. Depending on which copy of the book you read, you’ll either find French dialogue scattered throughout or a purely English translation.

“It’s insistence on the thought-worlds that are important to the cultures,” Professor Piatote said, referring to moments of resistance to translation in partially translated literature.

Two dominant theories circulate regarding the inclusion of French dialogue. One suggests that it served as a realistic portrayal of how Russian nobles spoke. The other points to Tolstoy using the language as a literary device to suggest elite artifice. Either way, you’ll get all the time you want to ponder about that as you dive into Tolstoy’s interrogation and exploration of his nation’s history.